journal: seaside and impermanence

on new beginnings and a bad book review of in the café of lost youth

Dear subscribers of the fruitless “The Upside South” (and newcomers, welcome!)

I’m trying something new. Something in me takes Beckett’s enduring invocation to heart every single time: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” I promise I’ll get back to him soon enough.

If you’re reading this inaugural post, this differs from anything I’ve done in the previous years, but a few of you—who knew me from my teenage years or mid-journalism school—will find familiarity in the tone and format. It’s all mine. Something I’ll endeavor to safeguard from A.I. It’s me on the curves of the eternal return, retracing my steps back into a place I only visited in my dreams.

This is my new newsletter, without journalism, marketing blueprints, politics, or clever big lessons. I’ll quote myself from the first version of the About page of this thing:

“This is an experimental newsletter — because I’d always like to be somewhere else, so I’ll write until I’m at a cafe in the old town of Brno. While I’m there, I’ll find myself dreaming again of the raging tropical storms of the Amazon, and when I come back here, I’ll be thinking of wandering through the houses of Saigon. Surely if you stick around long enough, we’ll end up somewhere together. Anywhere. Because I was born a writer and prayed countless times for relief, it appears God urges us to meet our fates resolutely and with grace. I’ll do it cowardly and with creatine in my coffee. He’ll understand.

I’m the avoidant in this relationship with the written word. Too much commitment, too many strings attached. So this time it’ll be a let’s see where it goes type of writing without the plans and formulas that had become the norm in my profession, which I managed to forsake (I graduated as a journalist and worked as a content writer for years, not that it matters at this point). Perhaps this is my attempt to find the latest, trendiest, coolest niche in writing; only this time instead of scouring the same top 10 blog posts about it, I’ll start following the little girl handing me ideas from the cellars of my heart. I’m not sure if it’ll pay the bills, and I confess I have been neglectful of this little kid…”

So stay if you’d like. Kindly unsubscribe if it’s not interesting. I won’t know and won’t come chasing you with a machete. The good news will always be: you’re free.

I was 8 years old when my mom asked me if I’d like to move to the seaside. I believe they wouldn’t have abandoned their plans had I refused. Mama was just being nice, and what kid would say no to that? She knew me. I had been to the beach twice before with my siblings and cousins. My first encounter with the Atlantic lies hazy in my head, but I vividly recall the warmth and strange beauty of having its colossal presence seemingly tethered by invisible barriers that kept it from engulfing us—a concept I grasped before learning about tsunamis, of course. Something anchored it safely, making very sure it stayed within bounds not to harm us. It felt like the ocean enjoyed our company just as much as we enjoyed being around it.

We moved, setting up the first major change in my life. At that age, I couldn’t comprehend that life would never be the same. Kids rarely think long-term or fully understand consequences. I was too enchanted by our larger home; the vines creeping over the front wall, and the little mysterious rooms in the backyard—one of which would become mine—along with the heavy wooden windows.

It all seemed very charming until they enrolled me in afternoon classes, and I suddenly had the freedom to wake up whenever I wanted. It felt strange. Afternoons used to be the time when kids roamed the streets, playing games and exploring the world until dinnertime. Then, we’d all retreat to our homes, only to return to the streets after dinner for more mischief (because we didn’t have cable back then). Well, that was gone, and gone forever.

I moved a few more times after that. The less thrilling move was when we relocated from the first to the fourth floor of the same four-story building. Although lacking the excitement of discovering new surroundings, I could spot the faint glow of streetlights casting shadows on familiar curbs, and there, amidst this landscape, was the window of my then-crush, beckoning from two buildings away.

The most exhilarating move was my first solo expedition when I dreamed of becoming some sort of Indiana Jones in Warsaw. To avoid taking the daunting leap of being little students in a distant land alone, I arranged to share an Airbnb with a young stranger from the English countryside whom I had never met. I’d get up from any of the six beds in the living room and spend some time staring at the walls of the old town, half-believing the red bricks and tourists. Andy taught me how to use sugar cubes in tea and have salmon with cream cheese on toast for breakfast, and I’m forever grateful for that.

The middle-tier thrill change came recently when duty called. Taking my mom, I found myself on a plane, going for a season with my older sister, who lives in the heart of the Amazon. Obeying, almost blindly, became a habit when life called. Now I had two boring flights ahead of me, and it might sound funny to you I say I had the brilliant idea to unearth my trusty old Kindle from its forgotten slumber, brushing away the layers of neglect like an archaeologist revealing ancient artifacts. I say brilliant because I can’t remember the last time I read a book as an obligation, and also because the light on top of the case doesn’t work anymore. Life has relentlessly battered my dreams in recent years.

An old friend, Amélie, once told the world, “Times are hard for dreamers”, but was there ever an easy time?

whatever happened in the café of lost youth

I learned about Modiano from a French professor who taught us about the creative Oulipian exercises and text transformations in a literature class, which I didn’t finish. In those days, I was in a bohemian phase, the rite of passage for some fresh high school graduates. “Wrong timing. This would have been a favorite a decade ago,” but back then, I lacked the audacity to explore French writers; I was only into movies and music. Instead, I found refuge with the English-speaking authors and Saramago, recommended by a dear friend, a blondie notorious for sleeping through classes. “It’s something else,” he would say, and he was right.

This time, I realized I was mistaken, though not immediately. I read this book twice in a row. It’s very short, and my two boring flights happened in the middle of a night I couldn’t sleep through. After finishing it the first time, I had a gut feeling that I was missing something. I couldn’t be that tired. I wasn’t sure if I missed the point, if the mystery was thinner than expected, or if my attention wasn’t properly divided between Louki and the whining dog in seat 10E.

I found the narrative too affected, too inclined to romanticize the blasé café scenario of Paris. It begins with a heartbreaking epigraph:

At the halfway point of the journey making up real life, we were surrounded by a gloomy melancholy, one expressed by so very many derisive and sorrowful words in the café of the lost youth.

(Guy Debord)

Jacqueline, also known as Louki, is the enigmatic protagonist and a focal point around which every inner life in the story seems to orbit. The book unfolds through the perspectives of four narrators connected to a café called the Condé, its free-spirited patrons, their myriad of minute obsessions, and their heavy bag of sorrows. Jacqueline’s upbringing, with her mother working as a dancer at the Moulin Rouge, shaped her into a wanderer, familiar with the city’s streets.

I initially struggled to empathize with her silent allure, which seemed to captivate nearly every man she encountered—the trope of cherchez la femme palpable on the pages. Yet, when she shared, “My only happy memories are memories of flight and escape. But life always regained the upper hand,” the irony of my situation dawned on me, and I was forced to look at her with the same compassion I looked at myself.

At first glance, the book appears to be about forgotten places, but most importantly, it’s an immersion in the lives of forgotten and forgetful people, now timidly attempting to reconcile reality with the dance between the unreliable fixed point of what was and the future that failed to preserve it. The madam who ran the café viewed them as stray dogs, which years later would end up struggling with the impossible task of reclaiming lost moments and easing unrelenting heartbreak through pure nostalgia.

It makes me think about the concept of the second death, that we die twice: once when we stop breathing and again when someone utters our name for the last time on Earth. I found a reviewer on Goodreads complaining about the number of street names in the book, suggesting it’s probably aimed at those readers familiar with or living in Paris. I thought so too, but now I see it as an attempt to immortalize these places, preventing them from fading into oblivion, much like the fate of the Condé, which eventually transformed into a leather shop.

George Perec captures the sentiment: “To write: to try meticulously to retain something, to cause something to survive; to wrest a few precise scraps from the void as it grows, to leave somewhere a furrow, a trace, a mark or a few signs.”

This liminality is explored throughout the book, starting from the bottom of Perec’s categorization in Species of Spaces. His idea of space begins “with words only, signs traced on the blank page,” then proceeds to grow in form and matter: a bed, a bedroom, an apartment, a building, a neighborhood, a city.

While the words in this book lack some credibility given the characters’ fragmented memories, they evolve into a symbiotic relationship between people and their ordinary spaces, something Perec calls the infra-ordinary. Similar to individuals, cities and neighborhoods develop distinct personalities over time and experience. The city becomes a character in itself, relying neither on the nuance of repetition nor the uniqueness of difference.

In my seaside town, there was a cozy pub tucked away on a quiet residential street known as On the Rocks. Across from the bar stood a solitary apartment building, followed by a few shops that only opened during the day. When the weekend rolled around, the street would get packed. We’d grumble at passing cars. No plans needed; if you showed up, you’d find your friends there. It was our go-to when we needed a break from home. During the pandemic, when I was living in Warsaw, On the Rocks closed its doors. After my return, I found my hometown changed. The countless tales of love, laughter, and drunken escapades are now just memories. On the Rocks was replaced by a commercial building housing multiple shops. The street itself lost its identity; it was known as the street of On the Rocks. Nobody knows its name anymore.

It was a street of answered questions.

This is a book of unanswered questions and unanswered people, after all, “We live at the mercy of certain silences.” It explores the concept of life changes from which we never fully recover—and we’re not supposed to, as per the wisdom of Heraclitus: “A man never steps into the same river twice.” Such changes leave indelible marks upon our souls, shaping us in ways we may never fully comprehend.

Just last week, as I caught up with childhood friends over a see-you-soon-beer, their reactions echoed their familiarity with my habit of sudden departures: “We haven’t seen you in two weeks and now you’re moving across the country? That’s so you!” They know I prefer emergence over arrival. In our younger years, my replies to their socials and gatherings would always be cryptic, something like “I’ll see what I can do for you.” Yet, within that subtle exchange of glances lies a tacit understanding, like a mild form of telepathy. We’d both immediately know whether or not I’d show up that day.

After I finished my second read and leg of my journey, a weary yet devoted voice caught my attention: “Hi honey, I’m almost home.” The man beside me. I noted his lanky frame and discomfort; I tried making some space, but his legs remained unmoved, a testament, perhaps, to his steadfastness. He gazed at his phone’s wallpaper—a picture of him and his husband—before drifting to the window until his eyelids caved in.

What must we do when we’re in the middle of journeys? In the confines of an airplane, we simply sit, perhaps offering a fleeting prayer to evade the 1 in 11 million odds of disaster and let things unfold. Harshly, this is not the approach we take to most of the complexities of life. There might be an underlying belief that no guiding hand or cosmic force is nudging us toward our destinations. We walk alone, standing on two feet, relying on our resolve. Unfortunately, most of us can’t fly planes.

Today’s changes are just different versions of what I’ve seen before, mere variations of the familiar; whether in the space of an aircraft or personal transformations, I face the immutable truth of our impermanence.

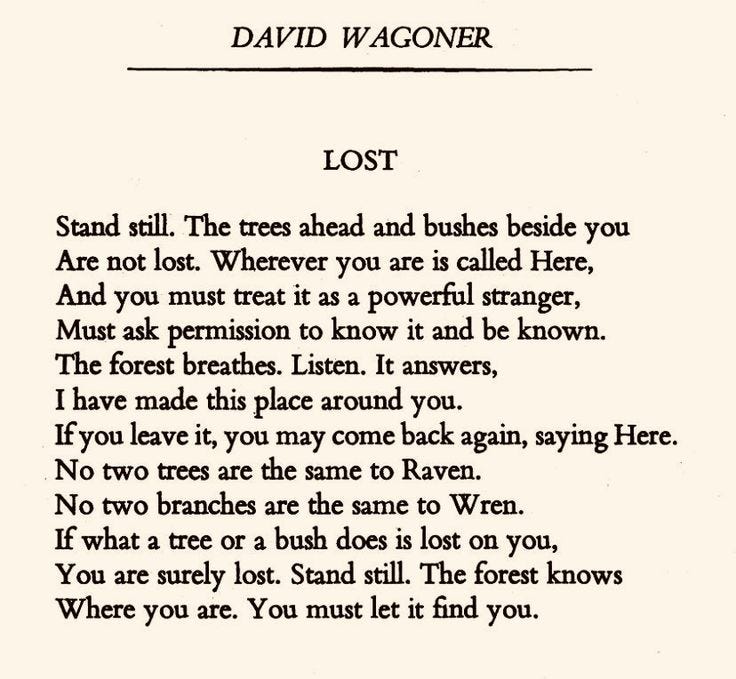

Changes ahead loom around the curve of time, waiting for us both to gravitate quietly, silently, down the same path on the fabric of the wisdom of the natural world. I could cave in as well and feel lost, but the instructions are clear.

What to do when we’re lost? Stand still. Let it find you.

— “Companions in unpleasant times,

I wish you the best of nights.”

Love,

everything is the same until it's not. here's to new beginnings and letting your inner voice guide you 🩶